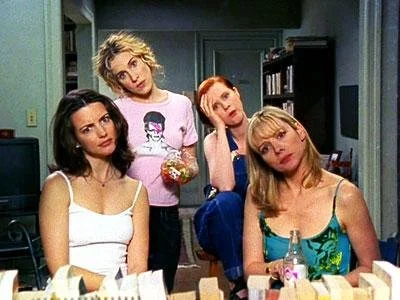

Sex and the City is 25

It changed the way we saw women on TV but was it actually feminist?

X

Sara O’Rourke

When Sex and the City hit the small screen, twenty-five years ago it created waves that changed the television landscape forever. Here were four women –in their thirties and unmarried, shock horror – talking about all the messiness of modern sex and relationships with honesty and candour. Today we talk about slut-shaming and sex positivity, and here we had Samantha openly pursuing boundless sexual adventures with utter confidence and Carrie and Miranda exploring the minutiae of their sexual lives in a way that was revelatory. The show won countless industry awards and remains a major creative influence – we wouldn’t have had the strong female perspective in iconic shows like Grey’s Anatomy, if it wasn’t for executive producer Darren Star taking the original novel to a then fledgling HBO, where the real way women talk could be expressed.

At its core, Feminism is about equality between the sexes, a statement that becomes more loaded and complex as our society’s thinking about those sexes/genders/presentations on the matter progresses. Let’s keep it simple – did Sex and the City work to serve the mission of women’s equality in an already male centred society. From the get go, we are very conscious of this 90’s New York microcosm being designed for and run by men, in terms of beauty standards and behavioural expectations of women. The idea of the show is that its characters are stretching the spaces left for them, by reflecting on and sharing experiences they were previously simply expected to endure, such as oral sex and passivity in romantic courtship. Throughout the seasons, the women knock down traditional expectations of women in their thirties, scoffing at baby showers and wedding registries, determined to carve out a life that suits them.

In the first episode we see the idea being acted out that to be equal to a man, you need to act like them, which has its own limitations. The struggle for power between Carrie and Big is a main plot thrust throughout, as well as who is in charge in each character’s relationship and whether that should be the case. Often there are moments when the women are definitely in charge, of who they date, what they tolerate, what they enjoy and their next move. Even Charlotte, whose role is mainly the sweet, hard to get coquette, uses her femininity to obtain certain behaviours from her partners, so she does want and manages to secure power in her relationships.

In TV land, men were allowed to be shown to be sexually active and pursuant while their conquests were simply grateful for the attention. The show reverses this, and we see the physical aspects of sex from the female perspective. Everything from obtaining orgasm, kinks and reproductive health is explored, in a way that serves the female – the characters want advice or seek to better their experiences. They also set boundaries that they expect to be observed, though these nineties women were with nineties men, who perhaps hadn’t gotten the memo yet about head pushing for oral and pressuring for anal sex. Sexually explicit language is run of the mill, allowing the characters to own their experiences and talk about them authentically. You could argue that the women objectify men in the same way they are being used to, as Samantha says, ‘Me, James, and his tiny penis, we’re just one big happy family’.

You’ve got to remember that Sex and the City looks at life under a particularly strict set of parameters. It’s a film noir-esque scene filled with slow jazz and cigarette smoke, where men and women are locked in their social castes, reduced to an eight-word personal ad and relationships are a game to be played. Within these restrictions, we can see more easily what patterns to subvert like for like – the ‘women doing it like men’ schtick is made plain to see, so on the surface you can read it as ultra feminism, look deeper and you’ll hit some snags.

Men and relationships are at the centre of their worlds. Sure it’s the focus of the show, but almost all those café confidential scenes have men as the topic of the day. Miranda famously criticises ‘How does it happen that four such smart women have nothing to talk about but boyfriends, it’s like seventh grade but with bank accounts…’ Would a more authentically feminist approach see the women trying to emotionally educate their partners? Of course we don’t get these deep conversations with men until the women are settled with serious romantic partners, but then those partners seem to undermine the women’s position. Steve forces high-powered Miranda to slow down, Harry undermining Charlottle’s high society expectations. And having all of them partnered off by the end, with the previously baby-phobic Miranda made a mother and forced to move out of Manhattan.

Intolerable men are tolerated, and the extreme materialism of the show does take the shine off a little. Our (slightly neurotic) heroines are white, het-cis, successful, and conventionally beautiful. This isn’t the story of the Everywoman. Unfortunately, we see the four seek validation from outside of themselves, from these intolerable men and all the shiny handbags their careers afford them. Carrie lowers her gaze from Big’s just a couple of times too many for today’s intelligent woman to buy any independence from men we’re supposed to believe she has.

Consistent fans who’ve now grown up and have complicated lives of their own, might still want to call the show feminist with a little ‘f’. The one major thing it did was put it up there, to be critiqued, to have women talk candidly about romantic life on their side of the bed, was a major step forward. In terms of the journey of the female narrative, it has its place. While what comes out of the mouth of many of the male partners might drive you mad, the female dialogue is peppered with cynical wit and tongue in cheek humour.

Twenty-five years is a very thick lens to look back through and really, you’d hope social expectations about equality would be more forward enough for past material to date as badly as this does at times. Sex and the City is wish fulfilment, it’s romance and it’s tongue in cheek. It’s not the feminist bible and it doesn’t need to be. What it does do, is create a platform for essential conversation about female sexuality and relationships, and today we certainly can’t have too much of that.